My goal for this post is to have a basic understanding of Calculus of Variations, so that I can be more comfortable with mathematics in NeuralODE paper, where the problem can be formulated as a optimization of a functional with ODE constraint (Adjoint State Method for an ODE).

My first encounter with Calculus of Variation is one of my homework where we try to derive probablity density function of some distribution by the principle of maximum entropy. This is my note of a more thorough investigation of the topic and it is heavily based on the content of this tutorial.

Similar to differential calculus where we try to find a stationary point, calculus of variations find a function to either minimize or maximize a functional (which is a function that take another function as argument).

Motivating examples

Shortest path between two points

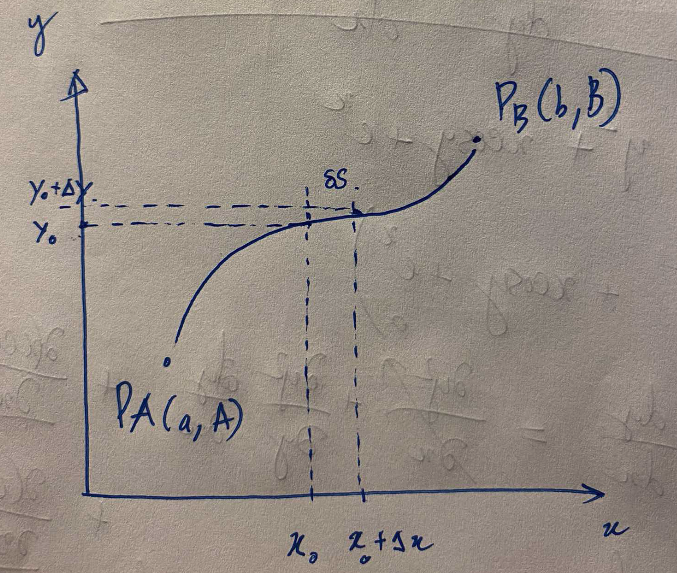

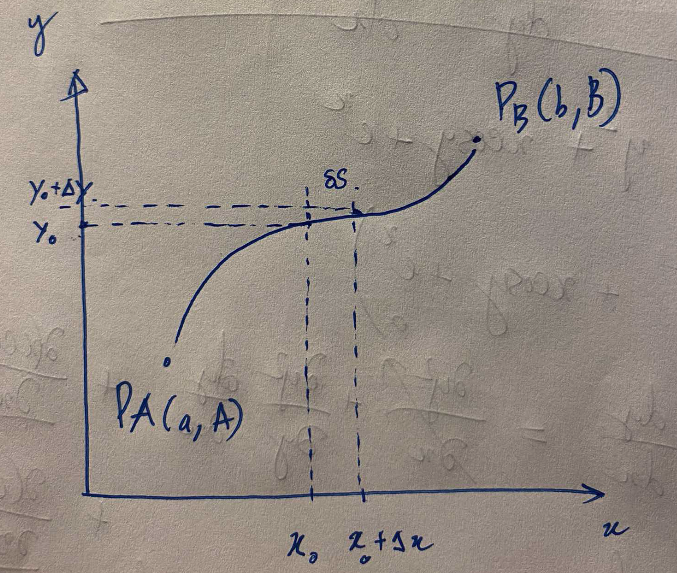

A path \(y(x)\) that passes two points \(P_A(a, A), P_B(b, B)\), so that \(y(a)=A\) and \(y(b)=B\).

Consider an infinitestimal segment along the path \(y\), the length of this curve is given by:

$$ \begin{equation} dS = \sqrt{dx^2 + dy^2} = \sqrt{1 + (\dot{y})^2} dx \end{equation} $$

Then the length of curve \(y\) is given by the sum of all \(dS\) along \(y\):

$$ \begin{equation} S[y] = \int_{P_A}^{P_B}{dS} = \int_a^b{\sqrt{1 + (\dot{y})^2}dx} \end{equation} $$

\(S\) is called a length functional of \(y\). The goal is to find function \(y\) to minimize \(S\).

Brachistochrone curve

A more exciting example would be the Brachistochrone problem, which was posed by Johann Bernoulli in 1696:

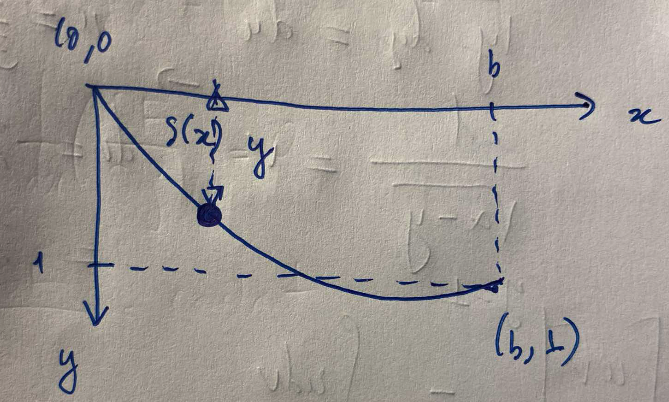

Given two points A and B in a vertical plane, what is the curve traced out by a point acted on only by gravity, which starts at A and reaches B in the shortest time.

The apparatus can be depicted in following diagram. In order to simplify the problem, we let two points \(A, B\) at \(A(0, 0)\) and \(B(b, 1)\) respectively.

The total energy of this system can be described as

$$ \begin{equation} E = \frac{1}{2}mv^2 - mgy \end{equation} $$

Where \(m, v\) is the mass and velocity of the point respectively. At \(t = 0\), both \(v, y\) are \(0\), so that the total engery of the system is 0. Due to the law of conservation of enery:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & E = \frac{1}{2}mv^2 - mgy = 0 \\ \implies & v = \sqrt{2gy} \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

Let \(S\) be the length of the curved traced out by the point, by definition of velocity we have

$$ \begin{equation} v = \frac{dS}{dt} = \sqrt{2gy} \end{equation} $$

For an infinitestimal segment of the curve \(y\), we have

$$ \begin{equation} dS = \sqrt{dx^2 + dy^2} = \sqrt{1 + (\dot{y})^2}dx \end{equation} $$

Substituing eq (7) into eq (6), we have:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & v = \frac{\sqrt{1+(\dot{y})^2}dx}{dt} = \sqrt{2gy} \\ \implies & dt =\sqrt{\frac{1+(\dot{y})^2}{2gy}}dx \\ \implies & T[y] = \int_0^b{\sqrt{\frac{1+(\dot{y})^2}{2gy}}dx} \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

\(T\) is the time functional of function \(y\), the goal is to find y such that \(T\) is minimized.

Euler-Lagrange equation

Let \(S\) be a functional of some function \(y(x)\) that go through two points \(P_a(a, A)\) and \(P_b(b, B)\), defined by

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} S[y] = \int_a^b {F(x, y, \dot{y}) dx} \quad y(a)=A, y(b) = B \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

Where is \(F\) is some function of \(x, y\), and \(\dot{y}\). The Euler-Lagrange equation states that in order for \(y\) to be a stationary path of the functional \(S\), the following equality must hold:

$$ \begin{equation} \frac{\partial F}{\partial y} - \frac{d}{dx}\bigg(\frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}}\bigg) = 0 \end{equation} $$

Derivation of Euler-Lagrange equation

Let \(\tilde{y}(x) = y + \epsilon \eta(x)\), such that \(\eta(a) = \eta(b) = 0 \) be some function that passes through \(P_a, P_b\). For \(y\) to be a stationary path of \(S\):

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & \frac{d}{d\epsilon}S[\tilde{y}] \bigg\vert_{\epsilon=0} = 0 \\ \iff & \frac{d}{d\epsilon}\int_a^b{F(x, \tilde{y}, \dot{\tilde{y}}) dx} = 0 \\ \iff & \int_a^b{ \frac{d}{d\epsilon}F(x, \tilde{y}, \dot{\tilde{y}}) \big\vert_{\epsilon=0} dx } = 0 \\ \iff & \int_a^b{ \big[ \underbrace{ \frac{\partial F}{\partial x} \frac{dx}{d\epsilon} }_{=0} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial \tilde{y}} \frac{d\tilde{y}}{d\epsilon} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{\tilde{y}}} \frac{d\dot{\tilde{y}}}{d\epsilon} \big] \bigg\vert_{\epsilon=0} dx} = 0 \\ \iff & \int_a^b{\bigg[ \frac{\partial F}{\partial \tilde{y}} \eta + \frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{\tilde{y}}} \dot{\eta} \bigg]\bigg\vert_{\epsilon=0}dx} = 0 \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

When \(\epsilon\rightarrow 0 : \tilde{y} \rightarrow y \), subsitute into equation 3:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & \int_a^b{\bigg( \frac{\partial F}{\partial y} \eta + \frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}} \dot{\eta} \bigg)dx} = 0 \\ \iff & \int_a^b{\frac{\partial F}{\partial y} \eta dx} + \underbrace{\bigg[\frac{\partial F}{\partial\dot{y}}\eta\bigg]_a^b}_{=0} - \int_a^b{\frac{d}{dx}\big(\frac{\partial F}{\partial\dot{y}}\big) dx} = 0 & \quad \text{(Integration by part)} \\ \iff & \int_a^b{\bigg( \frac{\partial F}{\partial y} - \frac{d}{dx} \big(\frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}}\big) \bigg)\eta dx} = 0 \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

Because \(\eta\) is arbitrary, in order for equality (4) to hold, quantity \( \frac{\partial F}{\partial y} - \frac{d}{dx}\big(\frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{}y}\big) \) has to be equal to \(0\).

\begin{equation} \blue{ \frac{\partial F}{\partial y} - \frac{d}{dx}\big(\frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}}\big) = 0 } \end{equation}

This equation is known as Euler-Lagrange equation. Any function \(y\) satisfied this equation will be a stationary path of functional \(S\).

Alternative forms of the Euler-Lagrange equation

Special case where \(F\) does not explicitly depend on \(y\) \(F(x, \dot{y})\)

Because \(F\) does not explicity dependence on \(y\), we have \(\partial F/\partial y =0\). By equation 12, it immediately follows:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & \frac{d}{dx}(\frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}}) = 0 \\ \iff & \frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}} = \text{constant} \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

First integral of Euler-Lagrange equation \(F(y, \dot{y})\)

Consider the total derivative of \(F\) with respect to \(x\):

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \frac{dF}{dx} & = \underbrace{\frac{\partial F}{\partial x}}_{=0} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial y}\frac{dy}{dx} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}}\frac{d \dot{y}}{dx} & (F \text{ does not depend on }x) \\ & = \frac{d}{dx}\big(\frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}}\big)\dot{y} + \frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}}\ddot{y} & \text{(Equation 12)}\\ & = \frac{d}{dx}\big(\dot{y}\frac{\partial F}{\partial\dot{y}}\big) & u\dot{v} + v\dot{u} = \dot{(uv)} \\ \implies & \dot{y}\frac{\partial F}{\partial\dot{y}} - F = \text{constant} \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

This equation is called the first integral of Euler-Lagrange equation.

Applying Euler-Lagrange equation to the motivating examples

Shortest path between two point on a plane

Reiterate that the path length of curve \(y(x)\) is a functional \(S\) of \(y\):

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & S[y] = \int_{P_A}^{P_B}{dS} = \int_a^b{\sqrt{1 + (\dot{y})^2}dx} =: \int_a^b{F(\dot{y})dx};\\ & y(a)=A, y(b) = B \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

From equation 15, we have

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & \frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}} = \text{constant} \\ \iff & \frac{\partial}{\partial \dot{y}}\sqrt{1 + (\dot{y})^2} = \text{constant} \\ \iff & \frac{\dot{y}}{\sqrt{1 + (\dot{y})^2}} = \text{constant} \\ \iff & \dot{y} = \text{constant} \\ \implies & y = ax + b \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

So the shortest path between two points on a plane is a line.

Brachistochrone problem

Time functional \(T\) of curve \(y(x)\):

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} T[y] = \int_0^b{\sqrt{\frac{1+(\dot{y})^2}{2gy}}dx} =: \int_0^b{F(y,\dot{y}) dx} \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

Using the first integral of the Euler-Lagrange equation, we have

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} & \dot{y}\frac{\partial F}{\partial \dot{y}} - F = c & \text{(c is some constant)} \\ \iff & \dot{y}\frac{\partial}{\partial{\dot{y}}}\big( \sqrt{\frac{1 + (\dot{y})^2}{2gy}} \big) - \sqrt{\frac{1 + (\dot{y})^2}{2gy}} = c \\ \iff & \frac{(\dot{y})^2}{\sqrt{2gy[1+(\dot{y})^2]}} - \sqrt{\frac{1 + (\dot{y})^2}{2gy}} = c \\ \iff & \frac{1}{\sqrt{y[1+(\dot{y})^2]}} = k & \text{(for some constant k)} \\ \implies & \dot{y} = \sqrt{\frac{h^2}{y} - 1} = \sqrt{\frac{h^2 - y}{y}} & (\text{for constant } h^2=1/k^2 > 0) \\ \implies & dx = \sqrt{\frac{y}{h^2 - y}}dy \end{aligned} \end{equation}

Let \(y = h^2 \sin^2\theta\), so \(dy = 2h^2\sin\theta\cos\theta d\theta\). Subsititutes this into equation 18, we have

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} dx & = \sqrt{\frac{h^2 \sin^2\theta}{h^2(1 - \sin^2\theta)}}2h^2\sin\theta\cos\theta d\theta \\ & = 2h^2 \sin^2\theta d\theta \end{aligned} \end{equation} $$

Take the antiderivative for both sides, we have

$$ x = \frac{h^2}{2}(2\theta - \sin 2\theta) + c $$

Finally, we have \(x = \frac{h^2}{2}(2\theta - \sin 2\theta) + c\) and \(y = h^2\sin^2\theta\), for some \(h, c\) determined by \(y(0) = 0, y(b) = 1\). In the tutorial, \(h\) and \( c\) can only be determined numerically.